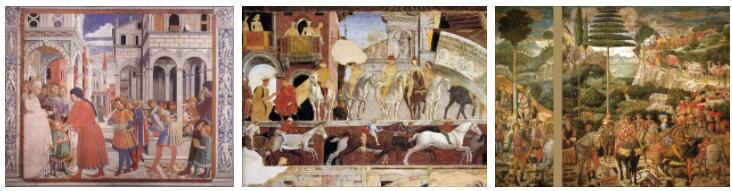

According to GLOBALSCIENCELLC, the last remnants of the Gothic tradition in sculpture were destroyed by Donatello (1386-1466), who for fifty years imposed his own art on Italy, as a national art. In his first works, the S. Giovanni Evangelista del Duomo and the Davide in marble from the National Museum of Florence, although not yet completely free from Gothic reminiscences, he knows how to achieve grandeur and plastic energy. In the statues of old figures, such as the Zuccone on the bell tower of the cathedral of Florence, he finds the opportunity to showcase profound anatomical knowledge, strong shadows, powerful muscles. Companion of Brunelleschi, he lives with him in Rome in search of classical architecture and sculpture; and these researches led him to square shapes, to master the straight line and to abandon the traditional Gothic convention. In Rome, Donatello is inebriated with ancient art which he disseminates in Florence, Padua, in the works of the Saint’s church and in those of all the artists who approached him; among others, Andrea Mantegna. In the bas-relief, which, especially in bronze, he treated extensively, from the baptismal font in Siena to the altar of the Saint in Padua and to the pulpits of S. Lorenzo in Florence, Donatello invented the pictorial manner, figuring the stiacciato forms from the first floor, and thinning them as they moved away within a space generally indicated and limited by architectural constructions. And, in the bas-relief, he achieved almost impressionistic effects of movement, for example in the dancing putti of the choir in Florence or in the little wild harpsichord player of the church of the Saint in Padua. Movement and construction of centralized compositions from perspective lead Donatello to create the human drama with a crudeness, a violence, a grandeur hitherto unknown to sculpture.

The Donatellian conquests dragged the immediate Florentine successors, who understood the dilemma: either to be Donatellian or to die.

Most of them did not have the daring soul, the indomitable strength of Donatello; they were simple, kind, delicate. They took advantage in part of the master’s conquests to express their little world; many of them had enough personality not to become slaves to his bullying figure.

Luca della Robbia (1400-1482), almost a contemporary of Donatello, was the most delicate and gifted Tuscan figurine maker; he spoke in the sweet country language; he placed his gentle and serious figures among wreaths of flowers and garlands of pomegranates and lilies, under arches of fruit that laugh in the blue. Naturalist without restlessness, of robust and healthy constitution, of simple customs, of good and mild nature, he did not look for subtleties, happy to model strong and beautiful Madonnas and boys. In 1441 he introduced colors for the first time in sculpture by means of glazing, which gave him the greatest fame. The Madonnas of the National Museum of Florence and of San Domenico di Urbino are the greatest examples of this form of art.

Other contemporaries of Donatello, such as Michelozzo Michelozzi, Pagno di Lapo Portigiani, Maso di Bartolomeo, were but a pale shadow of the master; Antonio Averulino, known as Filarete, an academic opponent of him.

The younger generation had a greater preference for grace than for the master’s energy; however, he almost always left. Simone, Isaia da Pisa, Andrea dell’Aquila, Urbano da Cortona, Niccolò Cocari, Giovanni da Pisa, Antonio di Chelino, Francesco di Valente, Pietro di Martino from Milan, Paolo da Ragusa, Domenico di Paris, Antonio Federighi, the Vecchietta, the Bellano, had in history the task of spreading Donatellian art throughout Italy.

A separate place, on the other hand, among Donatello’s followers, must be assigned to Agostino di Duccio and Desiderio da Settignano.

Agostino di Duccio (1418-1481) linked his name to the decoration of the Malatesta Temple in Rimini and the facade of San Bernardino in Perugia. Creator of shapes with a soft wavy relief, easy and imaginative creator of linear embroideries composed of curves upon curves, he dresses his figures in veil, folds them like rushes, wraps them in thin, tangled folds. His eyes narrow, the features of his face are sensitively thinner, the braids of his hair go around like ribbons, vibrate like tongues of flame on the round heads of the cherubs. The bodies go around, the tunics float, the basins of the niches open up like rays; everything sways in the wind, everything moves in cadence, creating easy festive rhythms.

Desiderio (1428-1464) appears less distant from Donatello; like Donatello, plastic is the soul of vibrations. Everything that is rough in the master disappears in Desiderio; what remains is the prodigious mastery of high and low relief and a rare ability to create elegant, graceful, sensitive forms. Architecturally noble, elegant, slender, as evidenced by the Marsuppini monument in S. Croce in Florence, revealing the grace of children like no other in the Tuscan fifteenth century, it gives an exquisite expression of intelligence, nobility, nervous sensitivity to female busts. flaking and wavy in the plastic planes. The acuteness in interpreting the model’s life makes him one of the most powerful idealizers of the Florentine feminine type.

The whole generation after Donatello seems to find in Desiderio da Settignano his highest expression of spiritual kindness and virtuous skill in dealing with marble. Luca della Robbia and, to a lesser extent, Bernardo Rossellíno (1409-1464) were the precursors of this new tendency to grace, just as Donatello, with a very different aim, was the master who prepared his technical ability, plastic wisdom.